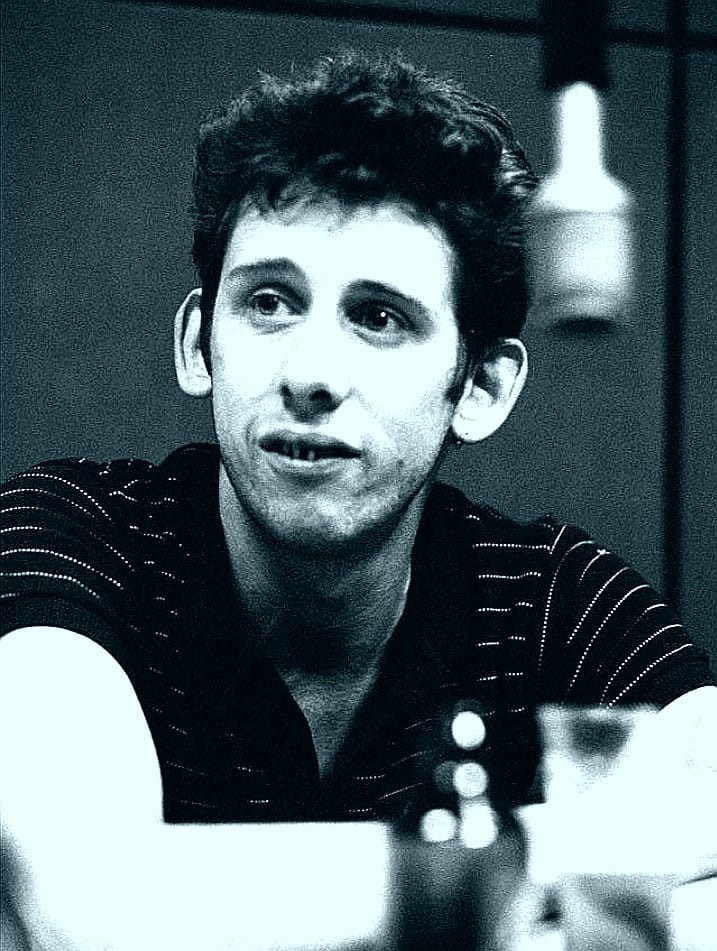

The Celtic punks The Pogues, born in the dirty pubs of London in 1982, drove the Irish tradition like an awl under the edge of punk rock. It wasn’t music — it was an autopsy of a dream, conducted to the accompaniment of drunken chords and a real frenzy. Their frontman, Shane MacGowan, is not a poet, but rather a chronicler of the social bottom, whose lyrics, smelling of whiskey and longing, go far beyond simple songs. These are full-fledged literary works, short stories about fallen scum, emigrants and all those whom civilization has uprooted and thrown into the trash of history.

The economy of their creativity is a black market of hope. They sang not about success, but about the cost of survival and the cost of falling. This is the soundtrack to the capitalist hangover, where the Irish immigrant is a bargaining chip in the big game of globalization.

The Pogues didn’t just mix genres — they created a musical revolution. Their sound was born at the junction of, on the one hand, the Irish folk tradition with its accordion, banjo and violin, and, on the other, the fierce energy of punk. They took folk songs about drinking, fighting and the hardships of life and put them through an amplifier charged with rage and despair of the “No Future” generation.

This sound has become the sonic equivalent of Irvine Welsh’s work — just as rude, honest and filled with black humor. Like the characters in “On the Needle,” the characters in The Pogues’ songs are marginalized, dreamers, and losers trying to find their place in a world that rejects them. Their music is the voice of the streets, factory outskirts, and train stations where those whom civilization has considered a marriage gather.

Here are ten songs by The Pogues that are worth listening to with whiskey in one hand and Joyce in the other.

1. “Sally MacLennane” – A hymn in honor of the goddess of stout

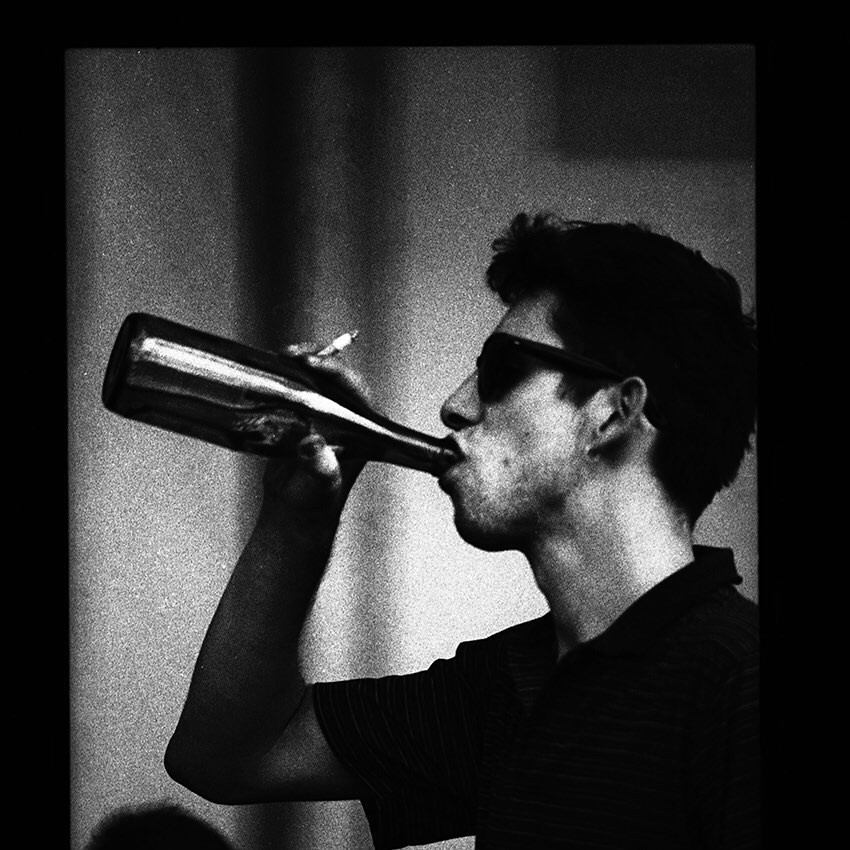

“Sally MacLennane” is not just an ode to a former lover. This is a hymn to his true muse, a strong stout. The song, inspired by Shane’s legendary drinking sessions in the bars around London’s Euston Station, is pure transcendental alcoholism.

“I was always a little jealous of Shane, it was almost a ritual: he’d get drunk and his friends would put him on a train to Ireland,” recalled accordionist James Fearnley.

It’s not just a song, it’s an escape economy — from longing, from London, from myself. MacGowan, who worked as a bartender, knew the value of both whiskey and words—he understood that both could be diluted, but why?

2. “The Old Main Drag” – London eats the soul

Produced by Elvis Costello, this song is one of MacGowan’s most poignant and merciless lyrics. This is not just the story of a young Irishman who came to London for hope and found only degradation. It’s an anti-musical about the capital of an empire grinding immigrants into mincemeat.

“Now I’m lying here, I’ve had too much / I was shat on, spat on, raped and abused.”

There is no romance here, just the raw truth of the London underbelly, served without embellishment. MacGowan does not judge — he states, turning a personal tragedy into a collective confession of a generation thrown on the sidelines of Thatcherism.

3. “Thousands Are Sailing” is an epic poem about exiles

Written by guitarist Phil Chevron after the band’s first stateside tour, this song is a monumental sound mural dedicated to the Irish diaspora. It directly refers to Ellis Island, through which millions of emigrants have passed.

But this is not nostalgia — this is an exploration of an inherited trauma. “The island is silent now,” Chevron wrote, and in this silence you can hear the voices of those who did not swim, did not reach, did not survive. It’s a ghost song, reminding us that the American dream was built on the bones of those it rejected.

4. “The Irish Rover” (with The Dubliners) – Pirate raid on folk Museum

Taking an old folk song, The Pogues and The Dubliners added punk rock, so that it soared to first place in the Irish charts. The story of a magnificent ship whose crew is killed by measles is an absurdist parable about the futility of any greatness.

The duet of MacGowan and Ronnie Drew from The Dubliners symbolized the passing of the baton — from the old guard of Irish music to the new, which was not afraid to rethink traditions, seasoning them with a fair amount of pirate spirit. It wasn’t just a cover — it was an act of cultural vandalism for the glory of the ancestors.

5. “A Pair Of Brown Eyes” – Waltz on the Ruins of War

The Pogues’ first single to hit the UK charts. MacGowan borrows the melody from the folk song “Wild Mountain Thyme”, but fills it with his own vision of a World War I veteran who, in a pair of brown eyes, seeks salvation from the nightmares of war.

“There’s an exhausted irony in his songs, as if he’s shedding light on dismemberment and the horrors of war; I’ve always liked that Shane’s songs have an inner power to hold the punch,” explained accordionist James Fearnley.

This is not a patriotic anthem, but an anti—war manifesto wrapped in a melody that makes you want to cry and drink.

6. “Dirty Old Town” – A hymn to industrial hell

Originally written by Ewan McCall (Kirsty McCall’s father) in 1949, this Salford song performed by The Pogues has become an unofficial anthem for everyone who grew up surrounded by factory pipes and broken hopes. MacGowan doesn’t just sing it — he lives it, making the story of a dirty industrial town universal for any place where dreams collide with harsh reality.

The Pogues didn’t just cover this song either — they appropriated it, proving that folk music is alive when it is sung by those who have the dirt of real life under their fingernails.

7. “Streams Of Whiskey” – Drinking as an act of resistance

If it only took one song to describe The Pogues, then “Streams Of Whiskey” would be perfect. This is their artistic manifesto, a declaration of intent, drunk to the dregs.

Released in 1984, the song captures the band at its most life-affirming moment. She aroused in the audience not just a desire to drink, but a desire to drink exactly the way Shane drank — with full awareness of the consequences, but also with the feeling that every sip was an act of poetry.

8. “If I Should Fall From Grace With God” – Punk Prayer of the Apostate

The title track from the 1988 album is the quintessential sound of The Pogues. After the success of “Fairytale of New York,” they could have gone down the beaten path, but instead released this frenetic, almost violent song.

This is a confession song about confrontation — with God, with oneself, with the expectations of the audience. This is the whole essence of The Pogues: the refusal to repent, the unwillingness to ask for forgiveness, the willingness to accept any fate, but to preserve their dignity.

9. “A Rainy Night In Soho” – A Ballad about love and booze

Initially ignored in favor of the more pop “London Girl,” the song eventually became MacGowan’s iconic ballad. This is not just a reflection on the breakdown of a relationship — it is a multi-layered metaphor.

Depending on the perception, it can be considered both an ode to long—lasting love and a metaphor for a relationship with alcohol – an unreliable, but so tempting companion. MacGowan is both a romantic and a cynic here, a poet and a drunkard — and in this contradiction is born the magic that makes the song eternal.

10. “Fairytale Of New York” (with Kirsty McCall) – Christmas for the Outcasts

Top. The absolute. An anti-Christmas Christmas song that has become an eternal classic. The duo of MacGowan and Kirsty McCall in the role of two downtrodden immigrants who find out their relationship in alcoholic oblivion is a three—and-a-half-minute Shakespearean drama.

“Tired of the string of tasteless Christmas singles that endlessly air every year, The Pogues wanted to write a Christmas song for people who don’t have the opportunity to have a good holiday.”

Ironically, this 1987 anthem of losers and outcasts failed to rise to number one on the charts, losing to the Pet Shop Boys’ synthpop cover of Elvis Presley’s “Always On My Mind.” Punk lost to the mainstream — a story as old as the world. But in this story, the losers turn out to be immortal.

The epilogue

The Pogues’ music is not nostalgia. This is a guide to survival in a world that tries to deprive you of your roots, voice, and the right to make your own mistakes. They didn’t sugarcoat the truth—they poured whiskey on it and set it on fire.

The legacy of The Pogues and Shane MacGowan cannot be overstated. They proved that punk is not only three chords and an orange mohawk, but also a centuries—old folk sorrow turned inside out.

Their music is not a nostalgic souvenir for hipsters. It is an emery that strips the varnished surface of reality to the wood of social ulcers, migration crises, and personal dramas. This is an eternal reminder that under the asphalt of megacities, living, suffering and jubilant human flesh still beats. And the next time the world seems too clean and right to you, turn on The Pogues at full volume, open the bottle and raise a toast. For those who fell by God’s grace. For those who were not taken to heaven. For Shane.

So turn them on to the fullest. Let the neighbors bang on the room heaters. Let the bourgeoisie grimace. Let the windows rattle to the beat of this drunken, furious, eternal frenzy. Glory to The Pogues! And may your own life be at least a third as vicious, poetic and beautiful as their songs.