To date, aerodynamics and automotive design have finally intertwined with each other into something relatively vile – flattened, rounded shapes that hurt the eyes have captured all the factories in the world, finally displacing individuality and character from a modern car. But a hundred years ago, no one could have imagined how an attempt to deceive air resistance could end. Moreover, it seemed like a great idea.

The thing is that at the dawn of the automotive industry, everyone was happy with the fact that a cart was traveling without a horse. But this quickly became insufficient for speed lovers and smart people who knew that air is a liquid. Someone just wanted to drive as fast as possible, someone was already trying to make the engine more efficient and save fuel, and someone did not think about anything like that, but was firmly convinced that the car and the airship should be similar to each other, since they exist in the same environment. Anyway, the first aerodynamic prototypes appeared back in the 1910s. They were not intended for the general public, but the engineers knew about them and nodded approvingly, winking mischievously at each other.

The first mass-produced aerodynamically efficient car appeared in 1921: at the Berlin auto show, the famous innovator, engineer, designer and constructor of airplanes and cars in general and the first Tatra in particular, Edmund Rumpler presented his Tropfenwagen, whose drag coefficient was only 0.28. For comparison, if you do not take into account the prototypes, then Among modern production cars, one of the most aerodynamic will be the Tesla Model S – its drag coefficient is … 0.24.

Tropfenwagen also incorporated several other advanced solutions, including the location of seats between the axles of the car: at that time, the rear seat was often located directly above the rear axle, which, coupled with the distribution of 65%-75% of the weight on the rear wheels, often meant not the most comfortable ride for passengers. But, despite all the revolutionary nature, the people did not accept the car – and one of the main reasons for this was the unusual appearance, scaring off a potential buyer. In total, about a hundred Tropfenwagen were built, at least two of which were burned down in the incomparable film Metropolis. And, unfortunately, the same fate befell many of Comrade Rumpler’s recordings and research – indeed, he himself almost ended his life in the same way. The fact is that power in Germany in the 30s passed to a man named Adolf, and Edmund, by the will of fate, was born a Jew. Numerous achievements in the field of German aviation saved Rumpler from death, but his career was ruined, and the Nazis tried very hard to put Edmund’s achievements into oblivion. Rumpler died in Germany in 1940.

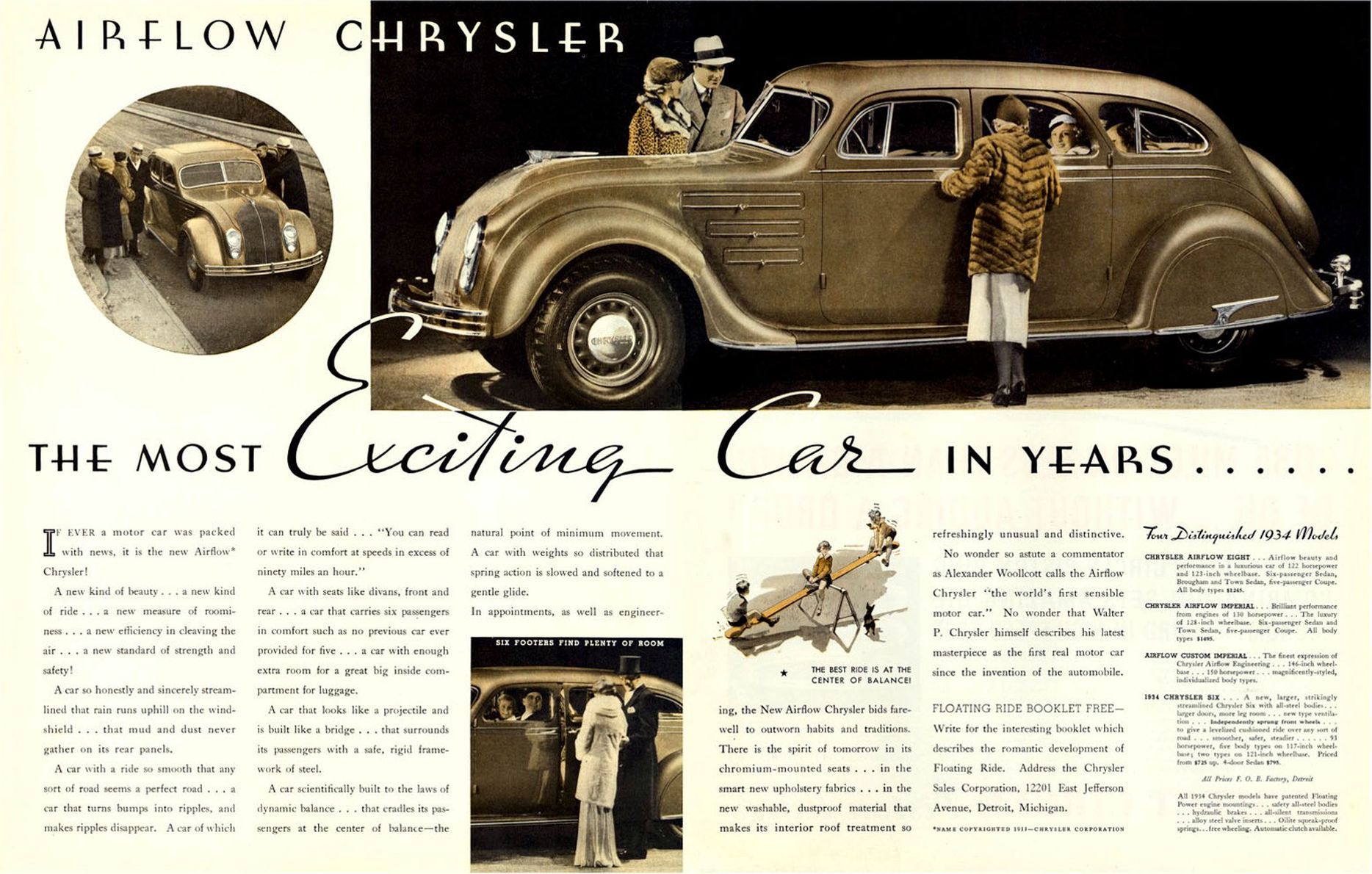

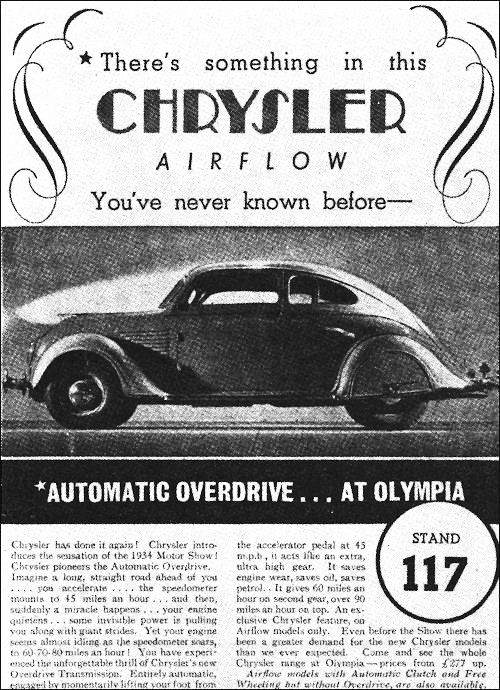

And a little more than ten years earlier, on the other side of the planet, Chrysler engineers Carl Breer, Fred Zider and Owen Skelton decided to bring an element of aerodynamics to the American automotive industry. It is impossible to say for sure how detailed Breer, Zider and Skelton’s knowledge of Tropfenwagen and other European cars was, but the three engineers began developing a new car almost from scratch: it is well known that Orville Wright himself was involved, in whose wind tunnel the first tests were conducted. By 1930, Chrysler had already built its own wind tunnel, in which further tests were carried out. In general, the car was developed for almost five years, and the result included, perhaps, everything that the streamliners had achieved at that time, and something else. In particular, the new car was frameless – it did not have a real load-bearing body like the Lancia Lambda released in 1922, but nevertheless, frameless cars in the mid-30s were still a very advanced solution. Chrysler engineers also achieved excellent weight distribution: the rear wheels accounted for 46% of the load, which, together with luggage and passengers, became very close to fifty.

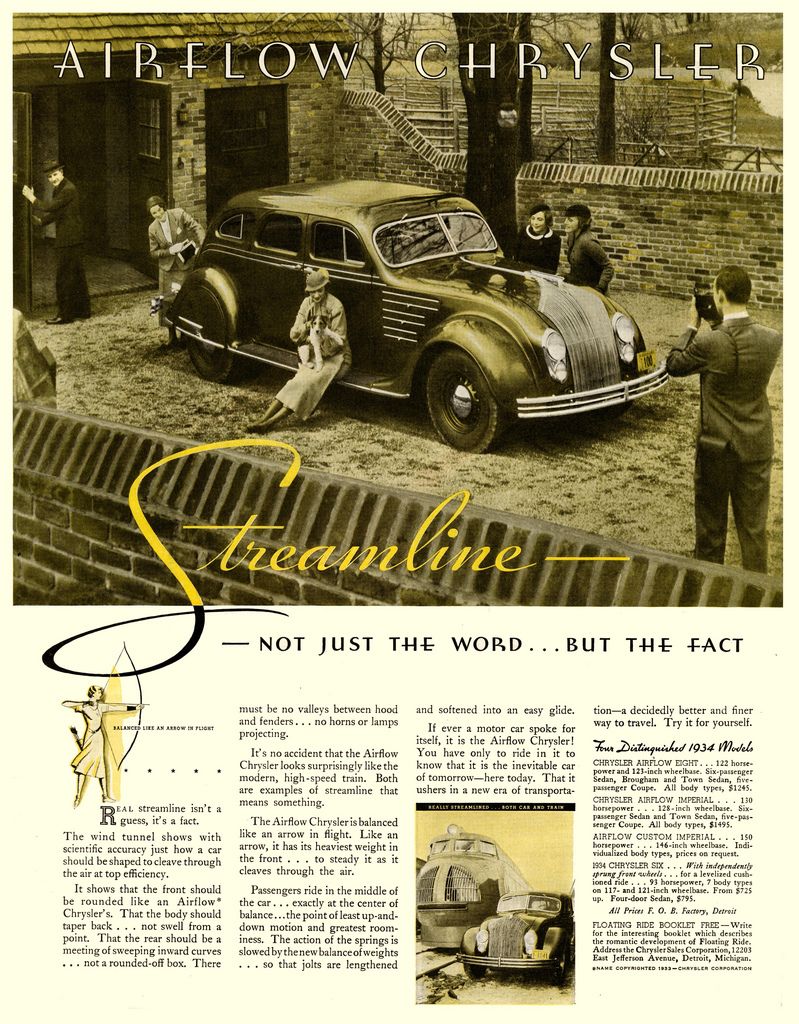

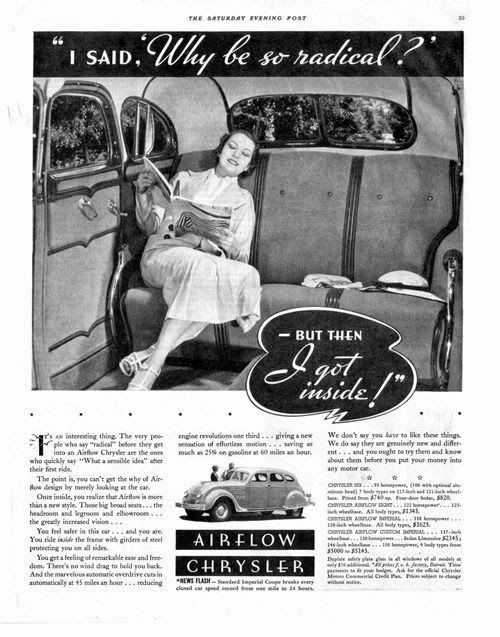

The commercial failures of fellow aerodynamicists in Europe did not frighten Chrysler – well, either the management simply did not know about them. Anyway, the corporation was confident of success, and began actively promoting a new car called the Airflow. Three promotional films were shot, including a trip to Bonneville, where a fully factory-built (according to Chrysler) Airflow set 72 speed and distance records, including a speed of 154 kilometers per hour on the flying mile and an average speed of 119 kilometers per hour over a distance of 3,200 kilometers. And to demonstrate the strength of the frameless structure, the car was thrown off a 35-meter-high cliff, after which the Airflow started up and drove away from the accident site under its own power. In addition, the advertisement included a public stunt involving a car driving backwards through the streets of Detroit: specifically for this, engineers swapped the axles and turned the steering mechanism 180 degrees on one of the 33-year-old cars.

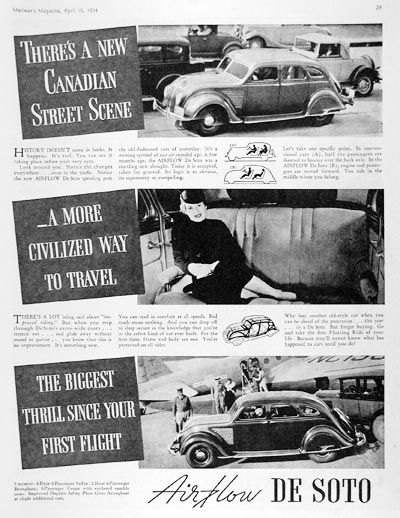

Perhaps the company’s management genuinely liked Airflow. Or maybe the big cats were just confident in the success of their marketing department. Anyway, it was like the roof was blown off for the guys from Chrysler, and they started making bad decisions one after another. First, the company decided to sell the new model under two brands at once – and everything would be fine, but DeSoto was not supposed to sell anything at all except Airflow. Secondly, for unknown reasons, the car was introduced in January 1934, a few months before it was put into production. As a result, by May, only 6212 cars had been assembled – in other words, it would be good if each dealer could have at least one Airflow. And, of course, the public didn’t like the look of the car: just like in Europe, an automotive culture had already formed in America, which Airflow didn’t really fit into.

And besides, despite the promotional films, there were rumors in the public that the new car was not at all as safe as Chrysler was broadcasting. Perhaps this was partly true: according to Carl Breer’s son, Fred Breer, the first two or three thousand Airflow left the factory with serious defects: at a speed of 130 kilometers per hour, the engine mounts could not withstand, which led to certain consequences. By the time Chrysler discovered the mistake, the image of the new car was tarnished.

By and large, Airflow failed miserably.Despite decent sales figures, the more traditional 33-year-old models sold two and a half times better – needless to say, Chrysler expected completely different results. Quickly throwing out the white flag, by the 35th year the company hastily redesigned the appearance of the car, trying to bring it closer to a more traditional design at that time. In a sense, we can say that only the Airflow of the 34th year is a real Airflow, and all the others are no longer the same.

Anyway, Chrysler continued to make changes to the car for several more years, after which it finally gave up completely. The Airflow was discontinued in 1937, and its fate mirrored that of Europe’s leading streamliners. For many years, Chrysler abandoned cutting-edge ideas and risky decisions – until the fifties, their cars would remain very conservative in many ways. It’s funny that Airflow was only a couple of years ahead of its time: already in ’36, sales of the Lincoln-Zephyr, an extremely successful and iconic American streamliner, began. In the same year, the 36th Toyota brand appeared in Japan: its first car was the AA model, whose similarity to the Airflow was never hidden – it is well known that before creating the first prototype, Kiichiro Toyoda bought one Airflow, disassembled it and studied it thoroughly. And in Europe, in 1938, sales of the Peugeot 202 began – and here it is worth mentioning that production of the car was discontinued only after the war, in the 48th year.

Perhaps, if it hadn’t been for an extremely unsuccessful start with falling out engines, the future fate of Chrysler and the entire automotive industry as a whole could have turned out completely differently. Nevertheless, it turned out what it turned out to be, and the Airflow of 1934 is, one way or another, a very significant point in history. That’s why I was very pleased to see the hot rod built on the basis of the DeSoto 34th.

First of all, it should be mentioned that the car body is completely standard – it is not cut into sections, nothing is chopped off, no chop tops. The author was clearly trying not only to build a first-class car, but also to preserve a piece of history. Just appreciate all the small details! Even the dashboard is original, and although the instruments themselves have been replaced, they are all made in a single copy by the real gurus of this business, Classic Instruments.

And those parts of the car that deviate from the original design, I personally find very suitable for this particular car. The V-shaped windshield looks great without a partition. The bend of the 18-inch Colorado Custom wheels, it seems to me, perfectly emphasizes the general idea of the streamliners and the smoothness of the body lines. And the coloring from Carr’s Hot Rods & Customs, in my opinion, is excellent: the color combination is somewhat unusual, but working, moderately bright, with elements of both smooth transition and contrast.

Technically speaking, another achievement from Chrysler was installed in the car – the famous vintage Hemi with a volume of 5.4 liters. It is powered by a Kuhl 6-71 supercharger with a dual carburetor. Despite the possible power that can be squeezed out of such a power plant, speed is clearly not the main thing for this Airflow, as indicated by the automatic transmission and Air Ride air suspension on all four wheels.

And that is why the information about this car does not specify the parameters of speed, acceleration and horsepower, but indicates the fact that it has won many awards at various auto shows. This DeSoto Airflow is primarily a piece of history and a great example of how Chrysler engineers imagined the future of the automotive industry in 1934.

Sources:

https://www.mecum.com/lots/DA1116-256476/1934-desoto-airflow-street-rod / (November 2nd, 2016)

https://www.classiccarcatalogue.com/CHRYSLER%201934.html