Lotus founder and chief engineer Colin Chapman, who won 7 constructors’ cups in Formula 1 from 1963 to 1978, wrote a popular book for his time, “Build your own sports car for as little as 250” (“Build your own sports car for just 250 pounds!”). At that time, the cost of a car of 250 pounds (about $400) seemed as unrealistic as it is now.

The essence of the design was to assemble the frame according to a pre-prepared design and use the necessary parts from the donor car. Caterham has acquired a license to manufacture frames and assembly kits, refined the kit, making it complete and eliminating the need for a donor, and still offers kits for creating such cars out of the box. Their model became one of the first among the car kits known as kit car.

The essence of the design was to assemble the frame according to a pre-prepared design and use the necessary parts from the donor car. Caterham has acquired a license to manufacture frames and assembly kits, refined the kit, making it complete and eliminating the need for a donor, and still offers kits for creating such cars out of the box. Their model became one of the first among the car kits known as kit car.

The editors of Car And Driver magazine (the American version of Behind the Wheel) decided to assemble the 1997 Caterham Kit Car and see what happens. The editorial office of the publication already had the experience of assembling a Kelmark GTS worth $ 13,678 in 1979, then the guys realized that 10 people were needed for such an event: two assemble a car, and the remaining eight do not let them go for a beer.

Despite the apparent simplicity of the Caterham build, the vague instructions made this work an experiment that brought the team together, as if everyone had been shipwrecked or taken hostage. But at the end of the day – okay, at the end of a long few days – the car started up and drove off, everyone was happy and at the same time confident in the correctness of their assembly.

After studying all the available kit cars, the comrades from Car & Driver chose the one that, as it seemed to them, was unlikely to be half-finished and abandoned, forgotten in the garage under a tarp. For our intellectual colleagues, we explain: the simplest kit was chosen. It was a Caterham model. The kit cost $27,664.

In 1973, Caterham bought the rights to a British sports car called the Lotus 7 from Lotus. Since then, Caterham has been updating and improving the car. However, assembling a car from a kit can be tedious. In the case of Caterham, it was very easy to get confused by the annoying mix of metric and inch systems. But this can be expected from any car out of the box. Next is a direct speech from the participants of those events.

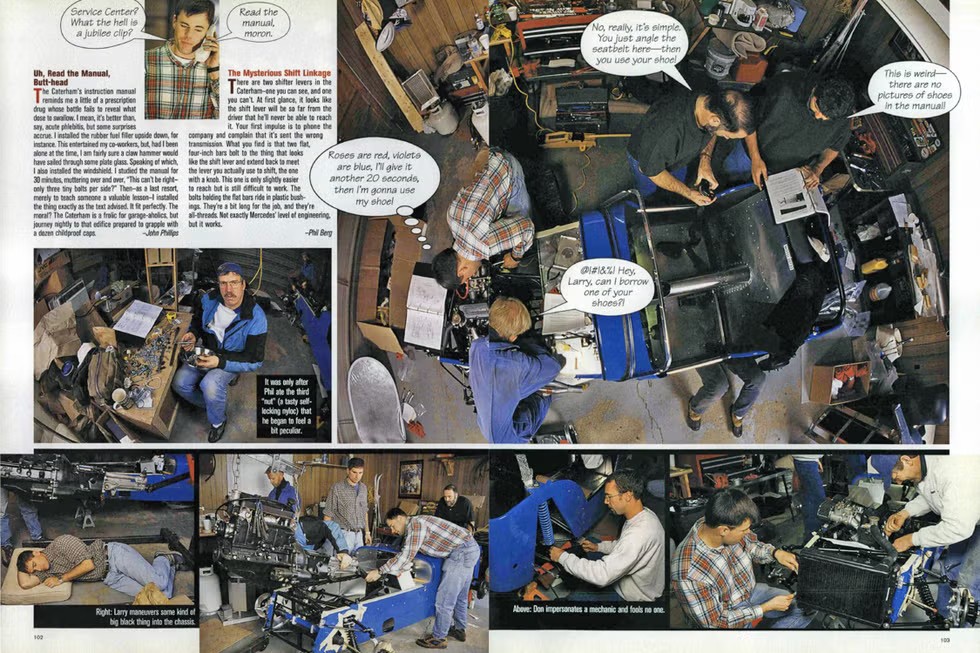

Read the instructions, stupid!

The assembly instructions reminded me of the medicine when the prescription doesn’t say how much to drink. So, I installed the rubber fuel pipe upside down, which amused my colleagues. However, I think if I were alone, I would probably smash some glass with a hammer. Then I installed the windshield. I studied the instructions for half an hour, muttering to myself: maybe there are only 3 small bolts on each side? In the end, I installed it as exactly as prescribed. Everything was perfect. The moral? Katerheim is fun for garage car enthusiasts, but when you embark on this erotic adventure every week, take protective equipment with you…

The mysterious gearshift lever

The Caterham has two gearshift levers — one you can see and the other you can’t. At first glance, it seems that the gearshift lever will be so far away from the driver that he will never be able to reach it. Your first wish is to call the company and complain that they sent something wrong. But then you find that two flat, four-inch rods are screwed onto a thing that looks like a gearshift lever and pull back to meet the lever you’re actually using to shift gears, with a so-called handle. It’s a little easier to get to, but it’s still difficult to use. The bolts holding the flat rods are in plastic bushings. They’re a bit long to work with, and they’re completely threaded. It’s not exactly Mercedes engineering level, but it works.

Problems? It’s always the ignition

Thirty years ago, before microchips took control of car engines, self-respecting car enthusiasts were thoroughly familiar with replacing spark plugs, interrupters, distributor capacitors, distributor caps and distributor rotors, as well as adjusting the idle speed and carburetor mixture. When the engine was running worse (or not working at all) after any manipulation, one rule had to be remembered: the problem is always in the ignition system. We almost forgot this rule when we first tried to start our Caterham.

There was no sign of a start, even after the mechanical fuel pump filled the carburetor to the brim and flooded the garage with gasoline fumes. First, we checked the orientation of the distributor, making sure that the rotor was pointing towards the spark plug wire No. 1 when the intake and exhaust valves of this cylinder were closed. Of course, the orientation really turned out to be incorrect, and after making the necessary adjustments, the engine started, but it worked unevenly. So we spent about half an hour adjusting the four mixture screws in the double side carburetor of the Weber. What we should have done was double-check the ignition order. The manual said 1-4-3-2. We had a 1-4-2-3 wiring. When we swapped the spark plug wires of the two central cylinders and dried the gasoline-soaked spark plugs, the Caterham immediately started and idled smoothly. As I said, it’s always the ignition.

Being a contortionist is also useful

The only thing more difficult than cramming a pair of legs and feet into a Caterham foot space is cramming your head and shoulders in there. This should be done to see where the ignition key is inserted (it is under the instrument panel), connect the wiring and design the handbrake. I say “design” because the manual only gives the vaguest hint of how the handbrake parts were supposed to fit into each other.

The closeness below also enhances the effect of carpet glue, leading to a state of euphoria. By the way, the carpet ends up wrinkling all over, because in the form in which it is supplied, it does not match the curved shape of the central tunnel and the gearshift housing. The seats, of course, don’t move. And the pedals in the Caterham are supposed to be adjustable, just like in the Dodge Viper. But after studying the instructions, we decided that installing adjustable pedals would require so much engineering and effort that it would make installing a handbrake look like screwing in a light bulb. It’s easier to just squeeze into the driver’s seat.

Sounds and fury

Surprisingly. It was 8:30 a.m., and all the engineers—Webster, Marcus, Schroeder, Idzikowski, and the chief hookmaker, Chere—were working in Webster’s garage!I thought they must have spent the night there. Schroeder was studying the car’s axle diagram, although I noticed that the instructions were upside down. Chere announced that 3/16 is his favorite wrench. (Who might have a favorite wrench!?)

Idzikowski, as usual, was trying to cram something into something that didn’t fit, and cursing. Some fool put all the nuts and bolts in a big bowl, and Webster stared at it, dumbfounded, with his mouth agape, as if the Secret of Life was hidden there. At 9:20 a.m., Phillips realized angrily that no one had brought a beer. In response, he spent four hours drilling six tiny holes in the sheet metal for the filler neck, and then collapsed. Smith arrived, tuned the radio to Golden Oldies, and went to take a nap. Phil Berg explained the theory of metal washers in Norwegian to an audience that, as you can imagine, listened to his every word. By noon, Marcus still had all nine fingers! Our photographer, the very strange Aaron Kiely, performed a series of simulations of canine flatulence without using his hands. Grinning, Idzikowski forced the engine to start. Chere said: “I’ll be right back.” Three to one, he went to wander the aisles of Ace Hardware in search of some 3/16 keys, and no one saw him anymore. I went out and bought 18 Italian oregano, olive oil, and vinegar sandwiches. Webster howled. “Hey, where’s the mayonnaise?” That’s all—I’ve seen enough.

The first trip brings the joy of parenthood

After 60 working hours spent in a cold garage, with sore backs and injured hands, after overcoming numerous challenges, the magic moment has finally arrived. Well, the truth is, Caterham was far from over, but hey, we needed some inspiration to prevent a volunteer mutiny. Therefore, without headlights, fenders and hood — on a cool day (it was about 0 ° C outside) — we did a few laps around the block.

After aligning the wheels in the old—fashioned way – by eye — we started the engine and crawled out of the garage. Delight! The car was actually moving on its own. It became even more joyful that pressing the brakes that had just been pumped stopped the car. Hey, we built this thing, and so far it’s working!

We carefully drove out onto the street and accelerated smoothly, keeping all our senses ready in case of unnatural noises or strange behavior. We braked to a complete stop again. Feeling a little more confident, we accelerated again and shifted into second gear. The engine said “blat-blat-blat.” We went. The car is turning! Is this how Henry felt with his Ford No. 1?

Even with the visual adjustment, the Caterham drove straight down the road, accelerating smoothly and stopping when we applied the brake. Moreover, we gained a little experience driving a Caterham car, which is not much compared to anything: a lot of power, little weight, wind in the hair (and teeth, and torso, and groin), terribly cramped interior. It gave us another boost of enthusiasm when we got back to work.

After another 40 working hours, we sent the finished car to a local auto repair shop for proper adjustment — solely as a precautionary measure.

The only way to really test our build was with a thorough beating, so we went to the track. The 626-kilogram Caterham made the most of its 135 horsepower. Without too much noise, it accelerated to ~100 km/h in just 5.4 seconds. It’s in the same league as the Corvette. The top speed was 169 km/h, and trust us, don’t approach that speed with a soft top installed. The assembly instructions also recommend not to do this, but we didn’t believe her and accelerated to the maximum speed, upon reaching which we were immediately rewarded with a terrifyingly loud “boom!” followed by the slamming of the roof. The plastic windows flew out. Dow!

Then there was a problem with the brakes — the rear wheels locked ahead of time, which caused the braking distance from 112 km/h to zero to 58 m. For such a light car, we expected something else, but we were sure that a little adjustment of the brakes would solve the problem.

However, success returned to us on the round court, where the car demonstrated a lateral acceleration of 0.94 g. The last Porsche Boxster we tested showed just 0.86 g.

Overall, we couldn’t be more pleased with the performance of the Caterham. Surprisingly, there wasn’t even the feeling that it was about to fall apart right on the move, which you’d expect from the cheapest build-it-yourself kit car. On the other hand, it’s only a stretch to call the Caterham a modern car. Security systems, for example, are only slightly less than completely absent.

And although it was our brainchild, it had its own peculiarities. Only those with ballerina-like legs will be able to control the pedals properly. Getting into a car is an exercise in office, and it’s terribly difficult not to feel vulnerable in a car that barely reaches the top line of most other vehicles’ wheels.

Characteristics of the Caterham car out of the box

1997 Caterham Classic SE

Vehicle type: rear-wheel drive, front engine, 2 passengers, 2-door convertible

engine

8-valve 4-row, metal block heads

Volume: 1691 cm3

Power: 135 hp at 6000 rpm

Torque: 165 Nm at 4500 rpm

TRANSMISSION

5-speed manual

DIMENSIONS

Wheelbase: 2.25 m

Length: 3.38 m

Curb weight: 626 kg

C/D TEST RESULTS

Acceleration to 100 km/h: 5.4 seconds

1/4 mile (402 m) drag racing: 14.1 seconds at 135 km/h

Acceleration to 100 mph (160 km/h): 16.3 seconds

Maximum speed (including drag): 169 km/h

Stopping distance, from 112 km/h to 0 km/h: 58 m

Acceleration on a 300-foot circle (92 m): 0.94 g

Results

In the U.S., Caterham kits range from an 84-horsepower Classic GT with a girder axle for $22,030 to a Sprint with De Dion suspension for $32,900. Those who are not adventurous can pay a Caterham dealer $2,500 to assemble the car at home. But that means you’ll miss out on the inner thrill of turning the steering wheel you’ve assembled, the joy of listening to the exhaust pulsating through the pipes you’ve carefully assembled, and the satisfaction of polishing the fenders you’ve installed with wax. If you are looking for an unparalleled car assembly experience, this is what you need.