Imagine for a moment that a ghost might have a voice. Not the pitiful moan that comes from the attics of Victorian mansions, but a deafening, furious roar born somewhere at the junction of a filthy basement, a cluttered garage and the last circle of hell. This voice is not a metaphor. This is psychobilly. And the film “The Last Subculture” by Kirill Ermichev is not a documentary, in fact it is a ghost cartography, an audiovisual session to summon spirits that we, in our conformist blindness, have long buried under a pile of simulacra.

“Russian rock”? Fire me. This drunken child, who grew up in the USSR, pulled on a jacket and began to read moralizing about “spirituality” while his original punk anger dissolved in a sea of quasi-intellectual posturing. This is the “money-oriented” subject of our early capitalism, voluntarily integrated into the cultural spectacle.

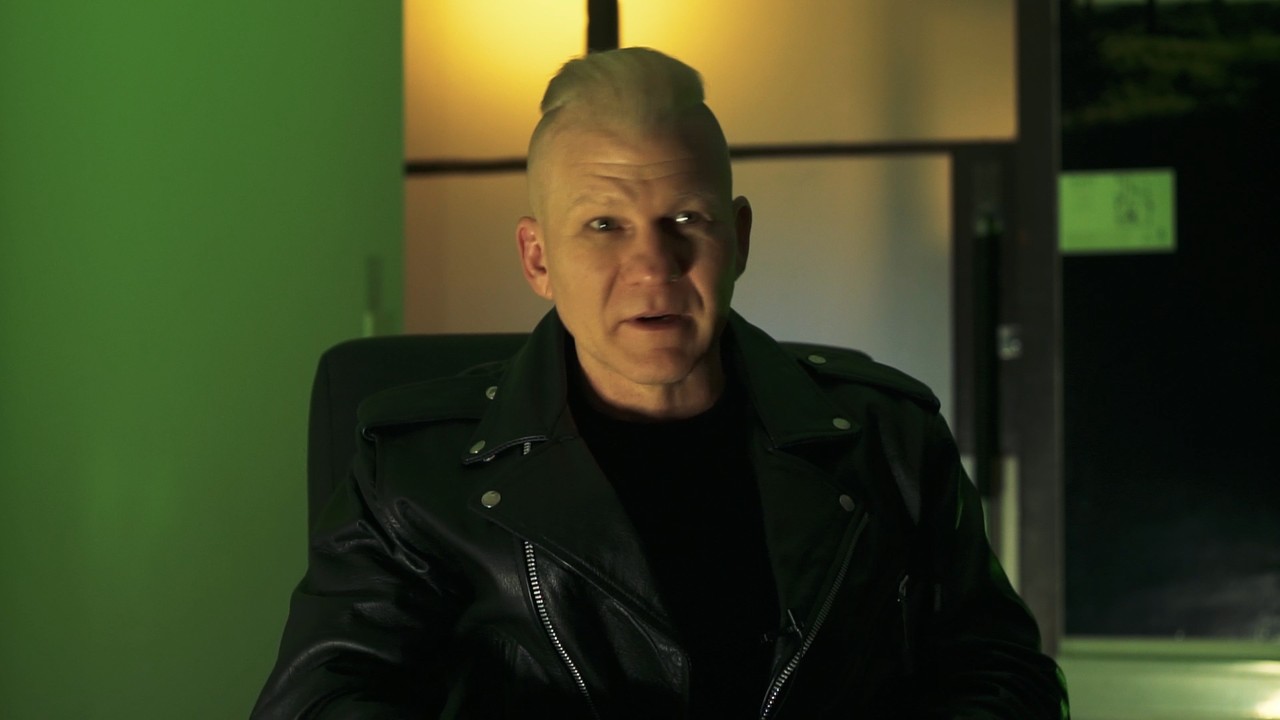

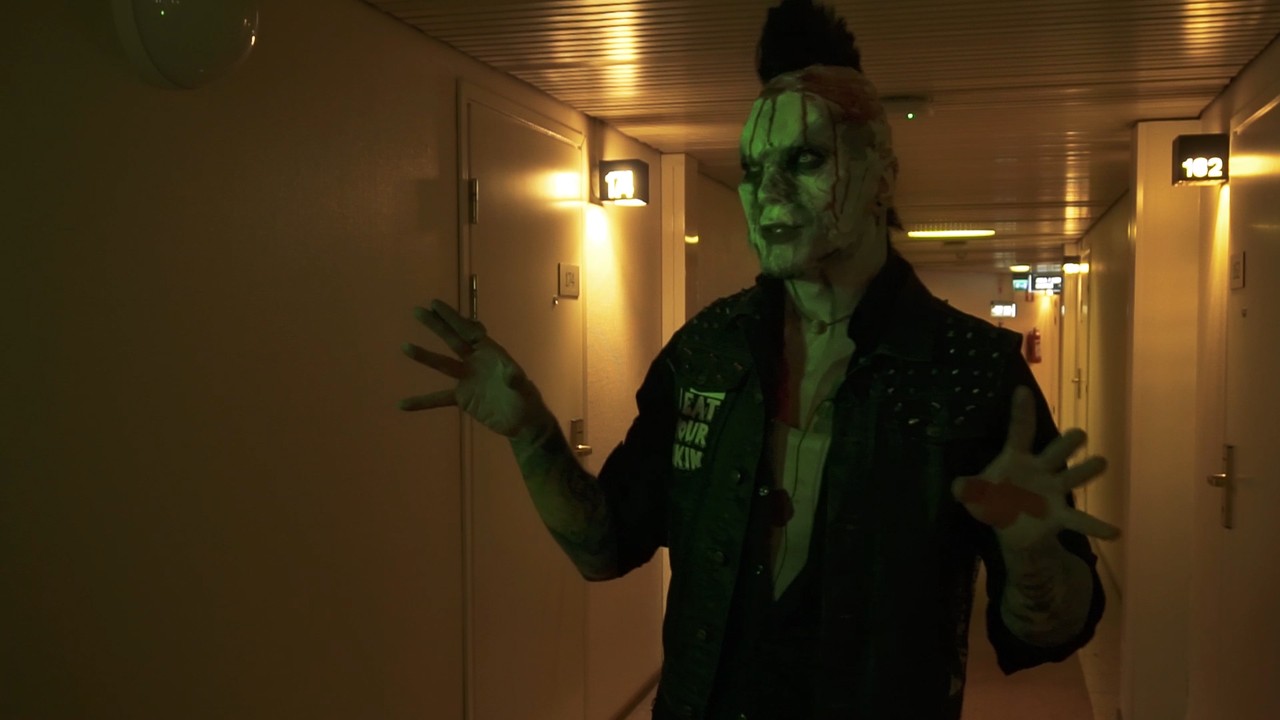

Footage from the film courtesy of Kirill Ermichev.

Psychobilly is its antithesis, its sonic anti-mainland. This is not a genre of music. This is a behavioral script of existential rebellion, written not with ink, but with saliva, and possibly someone’s blood. A mixture of punk, rockabilly and horror aesthetics is not a stylistic hybrid. This is a dialectical triple vinegar, corroding the very possibility of a smooth, marketed identity. One of my friends, the “fucking padonks in leather jackets,” once barked: “We don’t give a shit about your charts. We play because we can’t help but yell.” And in his painting Ermichev archives an act of symbolic creative suicide in a world where even protest has become a commodity. His camera catches not musicians, but cynics of the system, whose gesture — aggressive quarter-laptop, text-spell, image-ugliness — is the final and irrevocable “no”. “No” to political performances. “No” is a market logic that requires “digestible formats”. “No” is the very principle of meaningfulness in a world that has long lost its plot.

Psychobilly in Russia is an anomaly, a living corpse dancing at the disco of the end of history. In an era when, as Mark Fisher aptly remarked, “it’s easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism,” these guys are the ghosts of a future that never came. They are a reminder of that fork in the road where culture could have turned towards raw energy, but preferred the path of comfortable alienation.

Ermichev catches them in half-life mode: alive enough to frighten the layman, but already dead for the mainstream, which has long learned to digest and sell even the most radical gesture. Music market analytics is powerless here. These people don’t produce content. They produce noise — in the very information-theoretical sense, as a hindrance in the well-established signal of capitalist communication.

The very form of the film — 2 hours 15 minutes — is an act of resistance. This is not a “digestible format”. This is a marathon immersion into the zone of the impossible, a deliberate torture for the clip consciousness, which requires short rills and influencer smiles. This is zen self-torture, where the viewer, locked in the cinema, is forced to go through catharsis, even if he came “just to watch a movie about music.”

Let’s deconstruct this gesture. The quintessence of psychobilly, its symbolic order, is not a song, but a spit. A spit in the face of the system, taste, decency, understanding. But in a world where even spitting can be sold as an “action of radical art” or embedded in the rhetoric of “sincerity”, it is impossible to preserve the purity of this gesture. The genius of Yermichev’s film is that he does not even try to clean it up. He captures it in all its dirty, contradictory beauty. He does not show us heroes, but a symptom. A symptom of our collective longing for something real, even if this “real” smells of fumes, sulfur and a mental hospital. These musicians are not romantic rebels. They are pathologized clowns at the carnival of universal simulation, and their ugliness is the only remaining form of truth.

Punk conclusion and wish in the finale

So, what does Ermichev leave us? Not a movie. Not a story. He leaves us with an affective resonance, a sound funnel at the site of the exploded bomb called “marginal freedom”. Maybe tomorrow these last maniacs will be washed away by a wave of commerce, moralizers will strangle them, or they will simply die in oblivion, as befits living corpses. But while they’re dancing, we have to watch. To watch until the same pre-ontological primordial cry breaks loose in our own souls, polished to a shine by conformity.

Therefore, my intellectually sophisticated reader, after watching this movie you have only two ways:

Or you go home, put The Meteors on vinyl and enjoy smashing a bottle against the wall of your own cozy, well-appointed prison, feeling how for the first time in many years, not socially approved lemonade flows through your veins, but real, thick, vigorous-mother-her blood.

Or you stay sitting in a chair, dead inside, finally becoming part of the very machine that they hate with such sweet frenzy.

The choice, as always, is yours.

In the emotional battlefield

He’s fighting wars in his head…

The film is undoubtedly complementary, but no one intended to claim objectivity. In the opening narration, viewers who had read “Psycho-attack over Russia” unmistakably recognized the first paragraphs of its text and were almost slightly disappointed, expecting to see a live-action adaptation of the book.

Not so. Yes, the text is present, but solely as the cement that binds together the bricks of lines and reflections on the phenomenon from masters (Mad Sin, Reverent Horton Heat, Batmobile, Demented Are Go, Gorilla, Meantraitors, Loonapark, etc.) and, of course, Kirill Ermichev himself.

The story of the St. Petersburg psycho scene of the 90s, told by its participants themselves, penetrated the ears and souls of psychos and their admirers without any complex penetration. I don’t think it’ll resonate with casual viewers in the same way, but it might spark interest.

The concept is clear, and there’s no point lamenting the shortcomings of the film’s texture (like “what about these artists?”, “too little sloppiness and disgust with the mundane,” “why isn’t the theme of Korol & Shut’s friendship with the psychobillies explored?”). The music is excellent. What more do fifty civilized nonconformists need to get together and laugh at jokes that only they understand?

P.S. For some reason, fragments of the teaser for the yet-to-be-made film “Song of Real Indians” were included, apparently to somehow tuck the demo footage away. We all remember the success of the film “Psychos” with Kristina Asmus (we do, right?). I think he would have been a success in an alternate universe, where the 5th Column Meantraitors’ vision came to fruition and the domestic media world was taken over by tattooed thugs with double basses slung over their shoulders. It’s a relief that even in this less-than-ideal universe, they’re still playing their music, pushing their awkward, uncompromising ideas, and carrying their style forward. Which means the subculture won’t wither away completely.