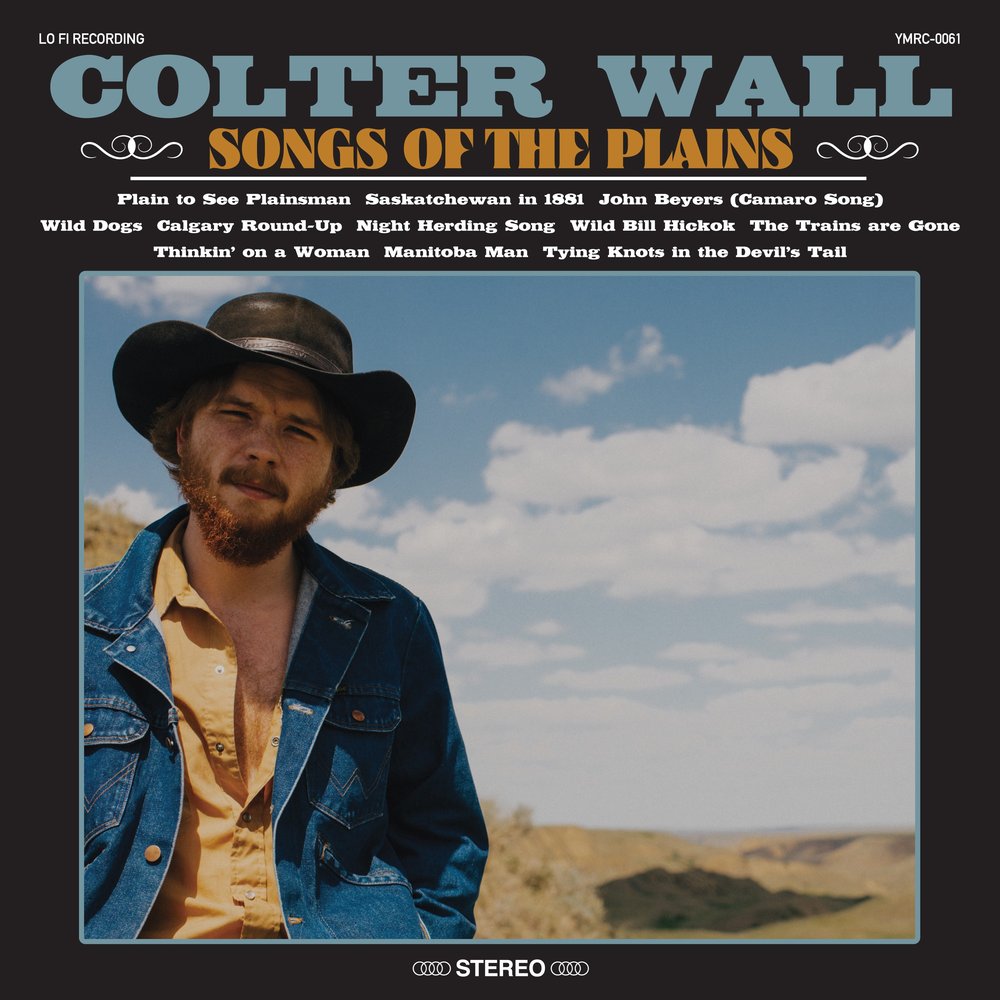

There are a lot of holes in the black tent of the old woman of the Night. Whose greedy little eyes are watching through these gaps for a homeless flock of wagons huddled around a campfire? Whose voice, trembling with hidden power, comes from this circle, lost in the Canadian Prairies? A hundred and fifty years ago it could have been him, his songs sound like that night a century and a half ago. Colter Wall. Where the hunting trails of Kris Kristofferson and Waylon Jennings run, he has trampled his own. For the first time, this unforgettable baritone shocked the audience somewhere in the province of Saskatchewan on June 27, 1995. The mother sang along with all her might – the birth was not easy, the boy was born immediately with a hat. After threatening the obstetrician with his dad, Colter took his boots and, girding his loins with a diaper, went straight home to master the guitar and ride around the wild wooden mustang.

The guitar didn’t take much time – after some twenty years, the first mini-album, “Imaginary Appalachia”, was recorded. The song from there, “Sleepin’ On The Black Top”, who could hear in witty films (I recommend watching them as well, but this will require additional organs) about the fate of workers: “At Any Cost” and “Three Billboards outside Ebbing, Missouri.” Wall’s powerful compositional and poetic talent was noted by the Unshaven and Terrible Rick Rubin, and the first full-length release, coincidentally the namesake of our hero “Colter Wall”, was published by the RCA giant in 2017. The Mustang has not been bypassed to this day.

The souls of murderers and cattle ranchers, hard workers and crooks are the ghostly threads from which the tapestry of the second long-playing album is woven. The sound of the plains stretching to the horizon, a companion with a dozen stories in two “peacemakers” is the ochre palette of “Songs Of The Plains”. Enough for a good picture and a good trip. Harness up, we’re leaving!

“Plain To See Plainsman” is a song by a tramp who has worn down more than one pair of shoes in his wanderings, his entire capital is memory and light sadness, and old bones that whine about reassurance in his native expanses. The penetrating sound of Colter’s iridescent baritone, the harmonica, distant, like a missed freight train – this song seems cozy and familiar, like a favorite shirt, like all the subsequent songs here.

The text of “Saskatchewan In 1881” will be relevant until Doomsday, I think, although it tells about the nineteenth century.

“Mr. Toronto,” says the hero of the song, “I gave enough grain, but it’s not enough for you. Don’t stick a pole on my doorstep, or the .44 will start rolling.”

This is followed by a description of the hard peasant labor and clever epithets addressed to the tax collector. Mentally and to the point.

John Beyers (Camaro Song) is dedicated to the dirty bastard John Beyers, who made holes in the 1969 Camaro belonging to the lyrical character. The revolver, the pedal to the floor, the anticipation of the Old Testament punishments. You can dance to it with pretty Missy.

Like a French piggy in search of a truffle, I can unmistakably smell musical masterpieces. Written by the venerable outlaw-country singer Billy Don Burns, “Wild Dogs” is beautiful in the original. And, as in the case of Johnny Cash‘s recordings for American recordings, it ceases to be perceived after Colter’s performance. A mystical journey through worlds and prairies to past lives. The pedal steel guitar, the companion of all wild dogs, trembles like the Northern Lights in the endless sky.

“Calgary Round-Up” is another alien song written by Wilf Carter, a famous Canadian country singer. A leisurely story about the Canadian Calgary Stampede rodeo, decorated with an imposing yodel. Wilf died a year after young Colter was born. Perhaps, passing by the Walls’ house, he was lucky enough to hear an early rehash of his composition.

“Night Herding Song” is a cowboy folk song. Sung almost a cappella, it was recorded around a campfire under the Tennessee sky so that the crackling of firewood and the sweet pulling feeling of loneliness can be clearly heard. It’s good for everyone to howl like a coyote from time to time.

“Wild” Bill Hickok was shot by the cowardly Jack McCall during a poker game, when, having betrayed himself for the only time, Hickok sat with his back to the door of a saloon in the town of Deadwood. Hickok had two aces and two eights in his hands, a combination later called the “dead man’s hand.” That’s how I ruined the intrigue of the story told in Wild Bill Hickok.

“The Trains Are Gone”, being another excursion into the history of the continent, in Wall’s own words, tells about changes, not always for the better. A harmonica mourns trains with the blues of rusting rails.

“Thinkin’ On A Woman” is a great classic country ballad dedicated to truckers whose hearts are trapped in the stagnant cabin air, and rye moonshine is unable to cure the languor of the spirit. Peasant lyrical.

The gloomy “Manitoba Man” lurked at a gas station, pouring fuel into tanks in daylight, poison into veins after dark. In the distance, Disaster rumbles with the inevitability of a scheduled freight train. American Gothic.

“Tyin’ Knots In The Devil’s Tail” is a broken cowboy two-step about the Human Enemy, sung by Wall together with his friends. The devil, as you know, has a lot in common with cows – horns, ears, hooves, tail… However, this does not justify the drunken trio from the song that lassoed the poor guy, sawed off his horns, branded him, and tied his tail in a knot. In modern times, the robbers would have been sued by lawyers, but then they simply rode off into the sunset with a bad whoop.

This is, in a few words, Colter Wall’s most recent album to date. Created in Nashville in 2018, produced by Dave Cobb, this sample of new country music with powerful roots testifies that we are looking at a future giant of the style, treading in the footsteps of the great elders of the past. It’s time for a rest, Moon Dogs!